An Enormous Study of the Genes Related to Staying in School

Researchers have found 1,271 gene variants associated with years of formal education. That's important, but not for the obvious reasons.

When scientists publish their research, it's rare for them to write an accompanying FAQ that explains what they found and what it means. It's especially rare for that FAQ to be three times longer than the research paper itself. But Daniel Benjamin and his colleagues felt the need to do so, because they work on a topic that is frequently and easily misunderstood: the genetics of education.

Over the past five years, Benjamin has been part of an international team of researchers identifying variations in the human genome that are associated with how many years of education people get. In 2013, after analyzing the DNA of 101,000 people, the team found just three of these genetic variants. In 2016, they identified 71 more after tripling the size of their study.

Now, after scanning the genomes of 1,100,000 people of European descent—one of the largest studies of this kind—they have a much bigger list of 1,271 education-associated genetic variants. The team—which includes Peter Visscher, David Cesarini, James Lee, Robbee Wedow, and Aysu Okbay—also identified hundreds of variants that are associated with math skills and performance on tests of mental abilities.

The team hasn't discovered "genes for education." Instead, many of these variants affect genes that are active in the brains of fetuses and newborns. These genes influence the creation of neurons and other brain cells, the chemicals these cells secrete, the way they react to new information, and the way they connect with each other. This biology affects our psychology, which in turn affects how we move through the education system.

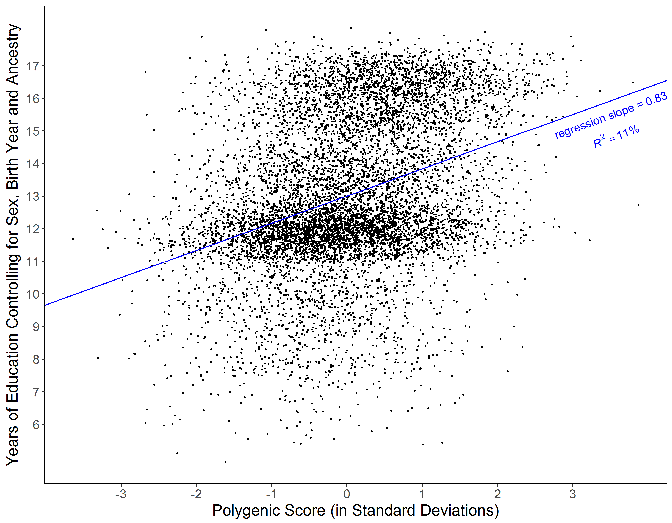

This isn't to say that staying in school is "in the genes." Each genetic variant has a tiny effect on its own, and even together, they don't control people's fates. The team showed this by creating a "polygenic score"—a tool that accounts for variants across a person's entire genome to predict how much formal education they're likely to receive. It does a lousy job of predicting the outcome for any specific individual, but it can explain 11 percent of the population-wide variation in years of schooling.

That's terrible when compared with, say, weather forecasts, which can correctly predict about 95 percent of the variation in day-to-day temperatures. But when it comes to predicting education, it's comparable to classic factors such as household income or how educated your parents are. "Within social science, that's basically unheard of," says Benjamin, who works at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. "We can explain education as well with saliva samples as with demographics."

"Education needs to start taking these developments very seriously," says Kathryn Asbury from the University of York, who studies education and genetics. "Any factor that can explain 11 percent of the variance in how a child performs in school is very significant and needs to be carefully explored and understood."

"If we can identify genetic risks for low cognitive ability, there is an argument for putting extra provisions in place to mitigate against that disadvantage," Asbury adds. "We already do that for environmental disadvantages, such as through additional funding or free school meals. I think we need to seriously consider the implications of biological risk factors and how a fair society should respond to them."

On the flip side, there are fears that this kind of research could lead to discrimination against, or stigmatization of, people with certain genetic variants. Such fears aren't unreasonable: Many forefathers of genetics were also proponents of eugenics, advocating that people with supposedly inferior genes should be discouraged from reproducing.

Paige Harden, a clinical psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin, thinks that neither these dystopian perils nor the more beneficent applications around personalized education are realistic. "I don't think that's where we are," she says, because one still cannot use a person's DNA to accurately predict their scholastic fates.

Benjamin and his colleagues agree. Look at the graph below, which plots years of schooling against subjects' polygenic scores. Each dot is a person. Sure, on average, those with higher scores got more education than those with the lowest. But for any given score, there are huge variations in years of schooling. "Should we use the score to put some people into more advanced classes and others into more remedial classes?" says Benjamin. "That's a total nonstarter because of the low predictive power for any given individual." The same applies to mathematical prowess, or overall cognitive ability.

And that's only for 1.1 million people of European ancestry. The score's predictive power is even lower for people of different ancestries, who likely have their own sets of education-associated variants.

"It's actually quite reassuring in showing that you could not accurately predict educational outcome from DNA," says Dorothy Bishop, a neuroscientist and geneticist at the University of Oxford. "The disturbing scenario of people screening babies in the hope of selecting the brightest does not seem supported by this study."

Indeed, Benjamin suspects that there's a ceiling of accuracy that his team has almost hit. Even if they study millions more people, he believes they won't be able to predict the educational fate of a single person with much more reliability than they can now. For that reason, the team have this to say in their FAQ:

What policy lessons or practical advice do you draw from this study?

None whatsoever. Any practical response—individual or policy-level—to this or similar research would be extremely premature and unsupported by the science.

So why bother doing the study at all?

One reason is to look at how genes and environments interact."If you did a study like ours 100 years ago, the strongest genetic predictor of education would be how many X chromosomes you had, because society was set up in a way that it was much harder for women to get educated than men," says Benjamin. Likewise, many of the genes that are associated with education today are likely important "because of how today's educational system is set up. It requires people to sit at desks for hours, and listen to instructions from a teacher. People who get restless, or are less obedient to authority, will fare less well in that environment."

Perhaps counterintuitively, Benjamin thinks that his team's research "is really important for research on improving educational systems." To understand how, forget genes for a moment, and think about wealth.

It's uncontroversial to say that people who are born into rich families are more likely to fare better in school than those from poorer backgrounds. Of course, poor kids can still soar in school, and rich ones can flunk out, but few would deny that money is a powerful influence on people's futures. Now, consider that household income explains just 7 percent of the variation in educational attainment, which is less than what genes can now account for. "Most social scientists wouldn't do a study without accounting for socioeconomic status, even if that's not what they're interested in," says Harden. The same ought to be true of our genes.

Imagine that authorities are planning to provide free preschool to kids from disadvantaged backgrounds. To see if such a policy actually helps children stay in school for longer, scientists would randomly assign the free classes to some kids but not others. Then, they would look at how the two groups fared. In doing so, they'd always try to account for factors like wealth that might also vary between the two groups. Similarly, "you can now wash away the genetic effects so you don't have to worry about them," says Benjamin. And in doing so, researchers could more precisely work out whether a policy change has any benefits—and they could do it through smaller, cheaper studies.

This, he argues, is the most powerful reason to study the genetics of education or cognitive ability—and ironically, it has very little to do with genes. Instead, it's a way of making social science more powerful.

The team is essentially studying genes so they can more thoroughly ignore them.

We want to hear what you think. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment